From Specs to Scaffolds: Why the One Prompt Template Is the PRD for the AI Era

PRDs gave teams alignment. Spec-driven docs give AI context. The One Prompt Template provides non-techies with a way to build software without feeling overwhelmed.

Why Building with AI Feels Broken Without Structure

Building with AI can be unpredictable.

Large language models that power CodeGen platforms and AI-assisted tools are inherently probabilistic in nature. To counter this, people are searching for ways to add structure, resulting in a well-designed, functional product rather than something generic or half-wired. The reason is simple: anyone who has tried knows how shaky the results of AI-generated apps can be.

You open a shiny new AI-assisted coding tool or a CodeGen platform, type something like “make me an app to analyze my daily journal entries for alignment with my year-long goals,” and what comes back is a half-wired mess. A login screen that doesn’t log in. If it does, it skips input validation. A dashboard assembled from mismatched components that fail to function as a cohesive whole, instead of a seamless part of the larger application. Error loops pop up every time you add something new, and the code is too opaque to tweak with confidence (a story for another time).

It’s not that the AI is broken. It’s the starting point that’s broken—your starting point.

In traditional software development, engineers would not write a single line of code until the specifications were established. Even before setting up bootstraps following initial discussions, teams relied on Product Requirements Documents (PRDs) to define the “what” and the “why” long before the “how.” Specs served as the antidote to chaos, ensuring alignment across business, design, and engineering (at least in theory).

Fast forward to the AI era, and suddenly, everyone can program. English has become the hottest programming language over the past two years, and this democratisation has opened a new gate: the need to figure out how to steer AI as we utilise CodeGen platforms and AI-assisted coding tools to build software products.

This gap hasn’t gone unnoticed.

Companies are already embedding structured planning into their AI tools to tame unpredictability from the start. One notable entrant, Amazon’s Kiro, enforces Spec-Driven Development (SDD) — a return to structure reimagined for the AI era.

Here’s the paradox: PRDs are too heavy, and even SDD—with its variations of required documents—quickly becomes overwhelming for non-techies entering the world of building with AI, whether via Vibe Coding or AI-assisted coding. Yet blank-box prompting is too loose. Non-techies are caught in the middle, either drowning in PRD-like Markdown files (the preferred format for AI) that are curated to steer the model, or guessing into the void.

Guessing into the void is not an option.

That’s why the real question isn’t “do we need spec documentation anymore?” It’s “what kind of spec docs do we need now?”

In the AI era, we don’t need less structure. We need a structure that is both simple enough for non-techies to use and robust enough to give AI the clarity it requires to build.

The Legacy of PRDs: Alignment Before Code

Before AI, before no-code, before agile sticky notes, software projects began with a document. The Product Requirements Document (PRD).

A PRD was never meant to be glamorous.

It didn’t instruct engineers on how to code or designers on how to design buttons. Its job was simpler and more powerful: to ensure everyone in a given project was building the same thing for the same reasons.

For the business team, it meant the strategic goal: What problem are we solving, and why now?

For engineers, it laid out functional requirements and constraints: What has to work, and under what conditions?

For designers, it described key user journeys and personas: Who is this for, and how should it feel to use?

For product managers, it defines the criteria for success: What qualifies as “done” and ready for launch?

In other words, a PRD was both a contract (here’s what’s in and out of scope) and a compass (here’s where we’re headed).

The roots of this practice go back to the 1970s with the rise of the Waterfall model, first described by Winston Royce. In that era, no code was written until a comprehensive Software Requirements Specification (SRS) was produced.

The SRS was exhaustive. It captured functional requirements, constraints, performance criteria, and user interactions. It served as the single source of truth for the entire project.

As software became increasingly commercialised and product management emerged in the 1990s, the focus started to shift. Requirements documents grew beyond technical specifications to include the 'why'—the target market, the user’s problem, and the goals the product aimed to achieve.

By the 1990s, the PRD was widely recognized as the key artifact of product management. In their 1997 essay Good Product Manager / Bad Product Manager, Ben Horowitz (a16z) and David Weiden (Khosla Ventures) underscored this by calling the PRD “the single most important document the product manager maintains.”

So the lesson is this: PRDs were never about bureaucracy for its own sake. Done well, they were about codifying clarity. They gave teams a single narrative to anchor their work before a single line of code was written.

And that principle —that clarity must come before code —is exactly what the AI era is rediscovering.

The Rise of Spec-Driven Development (SDD)

When CodeGen platforms and AI coding tools first emerged, their allure was undeniable: input an idea in plain English and watch software materialize. “Create stunning apps & websites by chatting with AI” is the promise of these CodeGen platforms.

For a few demos, that promise felt real. However, anyone who tried it for real-world projects encountered the same problem: raw prompting is too unpredictable. Plus, these days, credit is drained so quickly that you will feel the pinch before you even get something fully functional.

Tell an AI to “make me a task manager,” and it might give you a to-do list with no way to save tasks permanently, or a calendar that crashes the moment you try to edit an event — assuming it even wired a database to the front end in the first place. Each run feels like rolling the dice — a costly one, since you get charged even for the throw. That’s why professionals have begun to move towards a new approach: Spec-Driven Development (SDD).

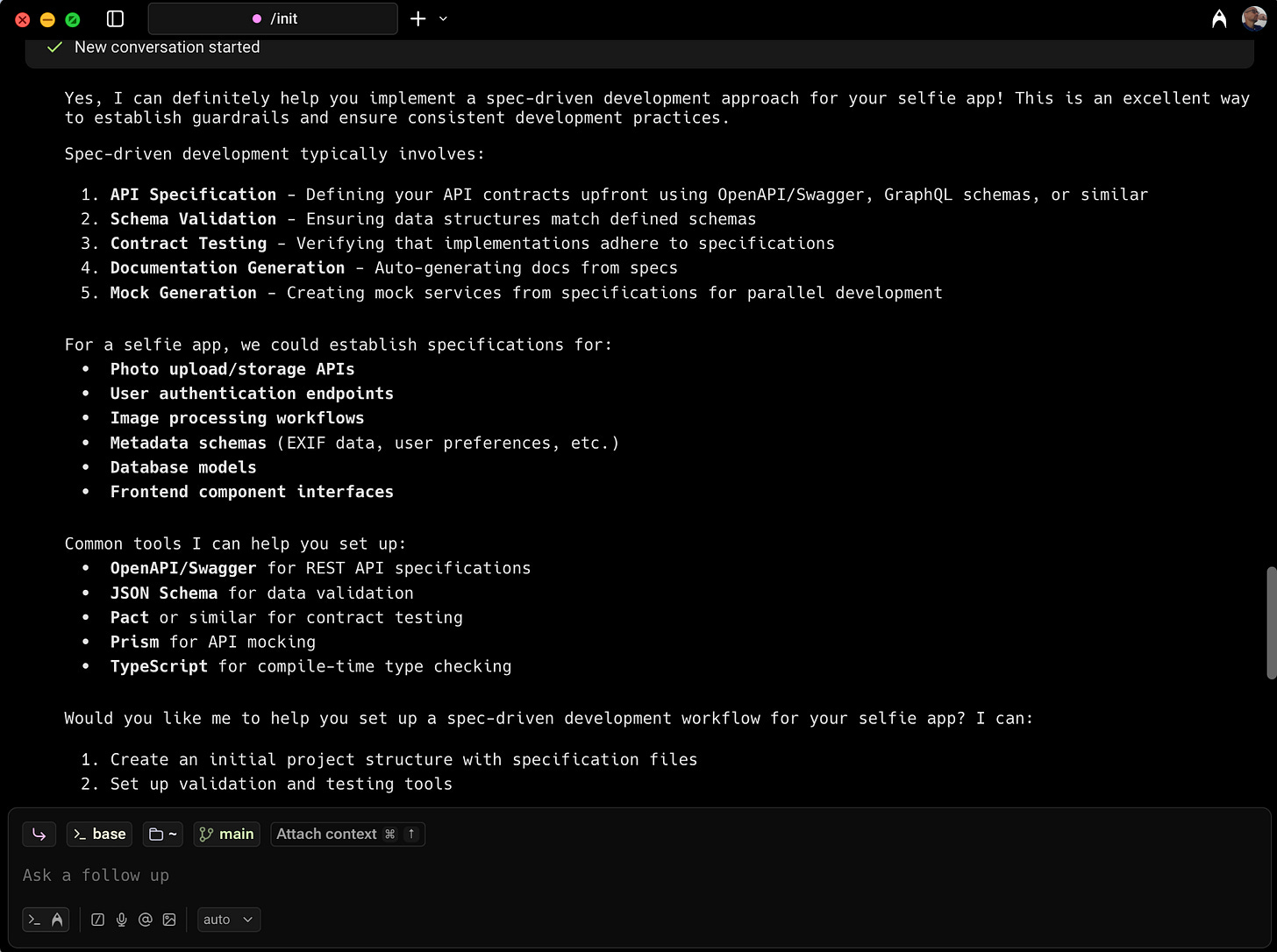

Instead of improvising instructions on the fly, SDD treats specs as super-prompts —structured, persistent documents that guide AI through every step of the build. These aren’t throwaway notes. They’re version-controlled, reusable, and designed to give AI the same clarity that PRDs once gave teams.

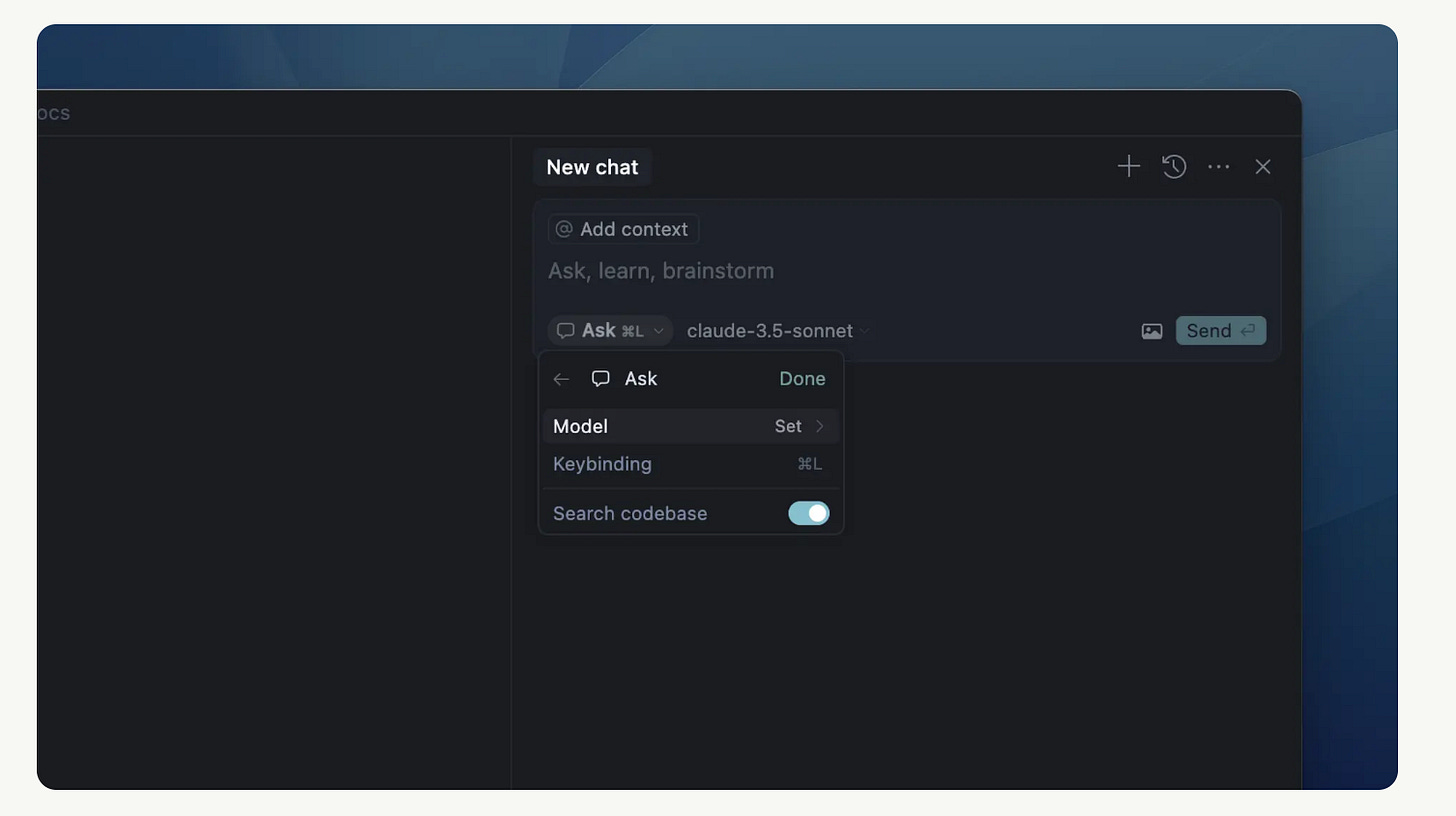

So, how does this work in practice? Kiro is the only platform with Spec-Driven Development integrated, but others like GitHub, Claude, Warp, and Cursor adapt their tools to support it in their own ways (not fully in its complete definition and purpose).

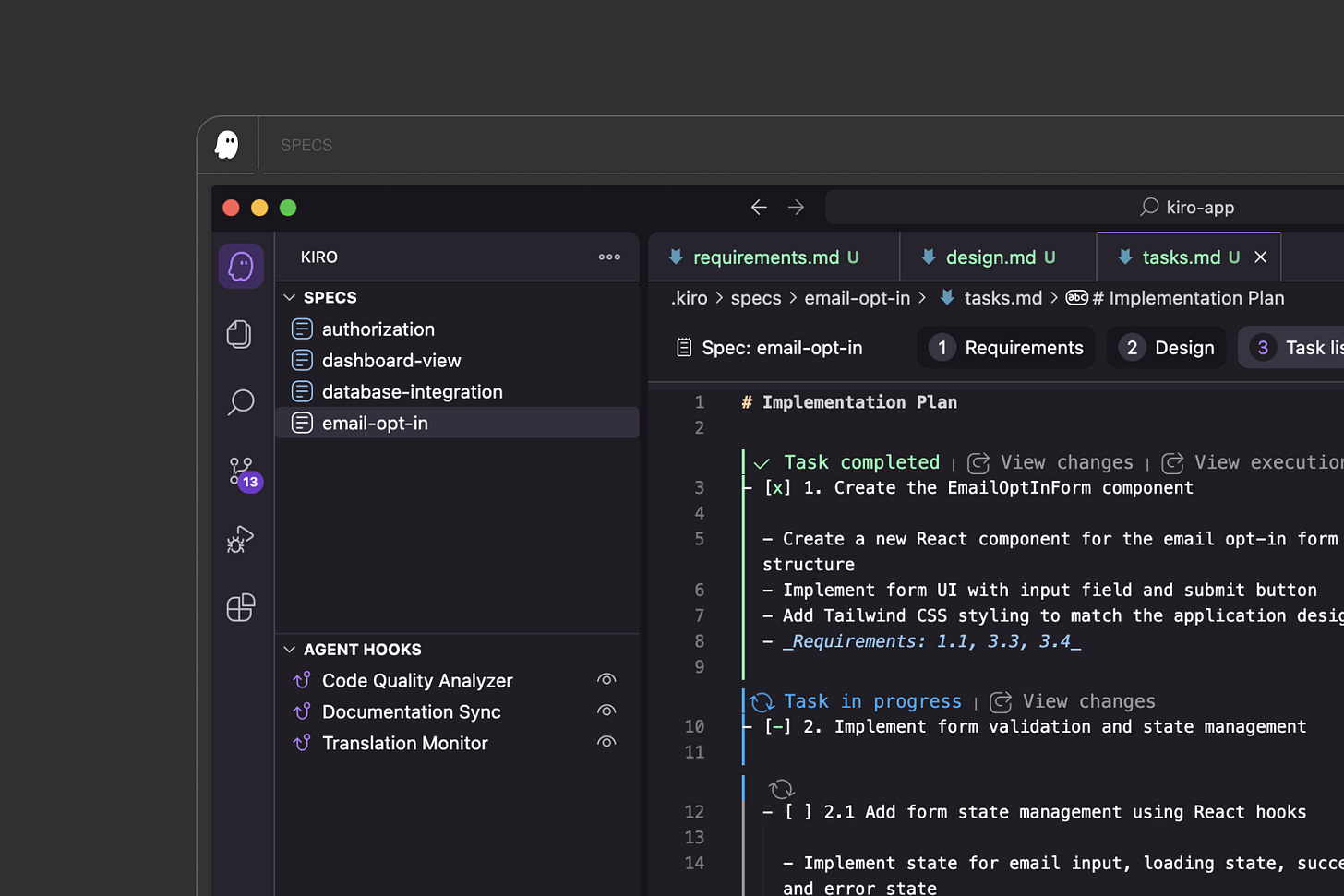

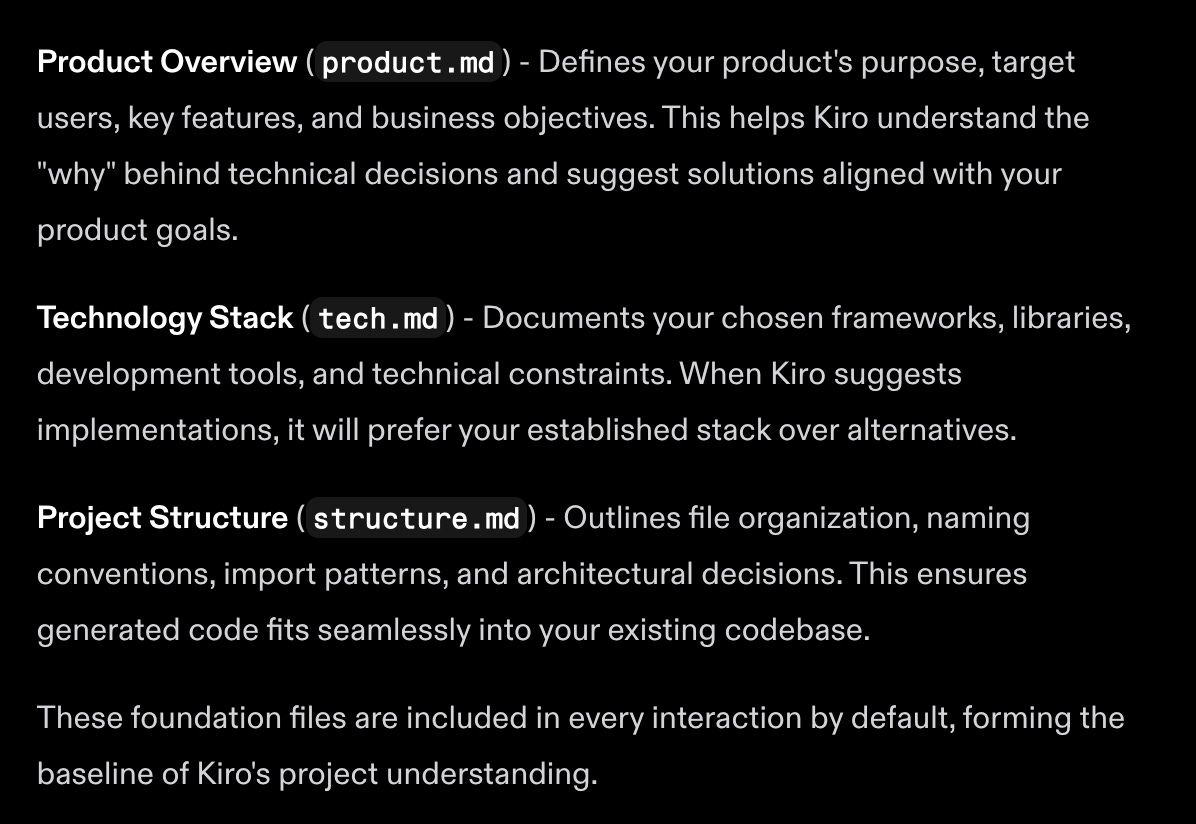

Amazon’s Kiro: built-in Spec-Driven Development using three steering files (product, tech, structure) that keep context persistent across builds.

GitHub’s Spec Kit: specs become drivers — you /specify, /plan, and /implement, turning the document into the OS of your build.

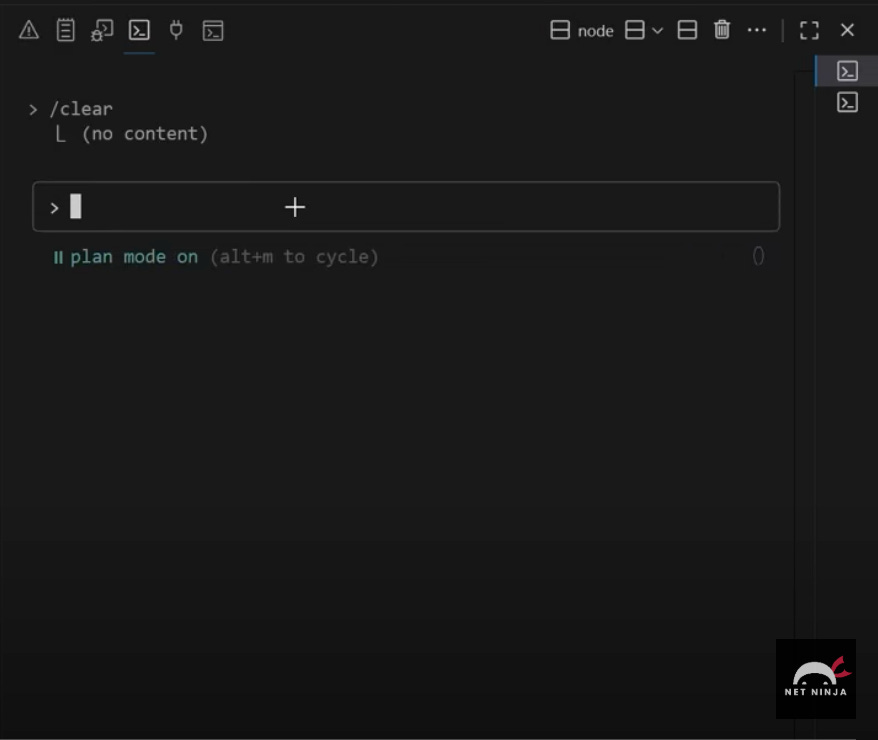

Claude Code Plan Mode: spec-lite planning that separates “thinking” from “doing,” forcing AI to draft a plan for approval before coding.

Cursor (Modes + Rules): workflow modes and version-controlled rules files give AI persistent context, a lighter form of spec-driven dev.

Warp: It doesn’t have a native SSD guardrail enforced built-in, like the others on this list, except, of course, Kiro. However, it provides a flexible environment where you can apply spec-driven practices.

Across the industry, the message is the same: structure is the missing layer between fuzzy prompts and reliable software.

But there’s a catch.

These spec-driven stacks are powerful, yet intimidating. For beginners, they can feel less like a launchpad for creativity and more like a wall of process.

That's why the One Prompt Template exists.

The Beginner’s Gap

Here’s the bind non-techies find themselves in:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Vibe Coding to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.